Sign up to save your podcasts

Or

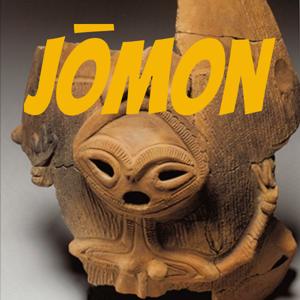

The pottery characteristic of the late Jōmon period was decorated by impressing cords into the surface of wet clay. Interestingly, the Japanese word Jōmon, literally, straw rope pattern; is derived from such decorations.

Due to warming climatic conditions, and the rudimentary practice of planting food-bearing trees and plants nearby their settlements, the Jōmon people enjoyed a relatively “sedentary” lifestyle and this era coincides with the production of the most extraordinary examples of their pottery (about 5,000 years ago).

Artistically speaking, this pottery, doki, seems too whimsical for the Stone Age. Some of these pots were used to store and cook food, but others appear far too elaborate for such uses. As human remains have been discovered in some pots, it is certain that the pottery had some ritualistic significance in the lives of the Jōmon people. Such pots may even have been akin to religious art.

Instead of offering a window on the past, these pots raise fundamental questions about how we perceive ancient cultures. Picasso famously said after viewing the cave art at Lascaux, “We have invented nothing new.” Collections of Jōmon pots definitely leave the same impression.

The pots where built up by successive layers of coils and then decorative elements were applied to the surface of the pots. From what modern researchers can gather, the Jōmon people did not bake their pots in a kiln, rather, the pots appear to have been baked on top of or under an open fire. While some pots are clearly meant for cooking, others were used for storing food. Furthermore, traces of lacquer have been identified inside pots which appear to have been used for storing foods.

Although the Jōmon had developed distinct styles for their highly decorative pots, their dogu, human figurines, have all the hallmarks of other prehistoric cultures. When you see the similarity between Jōmon figurines, Vinča figurines of southeast Europe, and Cucuteni-Trypillian figurines of eastern Europe, you can only imagine that humans, regardless of geographical location and local conditions, have similar tendencies. These simple, yet beautifully crafted figurines often celebrate female fertility. Thus, it is almost certain that such figurines had ceremonial significance in the lives of our ancient ancestors.

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Shiseki Umenokiiseki Park

By Shiseki Umenokiiseki Park

The pottery characteristic of the late Jōmon period was decorated by impressing cords into the surface of wet clay. Interestingly, the Japanese word Jōmon, literally, straw rope pattern; is derived from such decorations.

Due to warming climatic conditions, and the rudimentary practice of planting food-bearing trees and plants nearby their settlements, the Jōmon people enjoyed a relatively “sedentary” lifestyle and this era coincides with the production of the most extraordinary examples of their pottery (about 5,000 years ago).

Artistically speaking, this pottery, doki, seems too whimsical for the Stone Age. Some of these pots were used to store and cook food, but others appear far too elaborate for such uses. As human remains have been discovered in some pots, it is certain that the pottery had some ritualistic significance in the lives of the Jōmon people. Such pots may even have been akin to religious art.

Instead of offering a window on the past, these pots raise fundamental questions about how we perceive ancient cultures. Picasso famously said after viewing the cave art at Lascaux, “We have invented nothing new.” Collections of Jōmon pots definitely leave the same impression.

The pots where built up by successive layers of coils and then decorative elements were applied to the surface of the pots. From what modern researchers can gather, the Jōmon people did not bake their pots in a kiln, rather, the pots appear to have been baked on top of or under an open fire. While some pots are clearly meant for cooking, others were used for storing food. Furthermore, traces of lacquer have been identified inside pots which appear to have been used for storing foods.

Although the Jōmon had developed distinct styles for their highly decorative pots, their dogu, human figurines, have all the hallmarks of other prehistoric cultures. When you see the similarity between Jōmon figurines, Vinča figurines of southeast Europe, and Cucuteni-Trypillian figurines of eastern Europe, you can only imagine that humans, regardless of geographical location and local conditions, have similar tendencies. These simple, yet beautifully crafted figurines often celebrate female fertility. Thus, it is almost certain that such figurines had ceremonial significance in the lives of our ancient ancestors.