Sign up to save your podcasts

Or

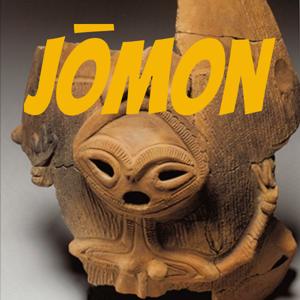

Due to warming climatic conditions starting some 6,000 years ago, and the rudimentary practice of planting food-bearing trees and plants nearby their settlements, the Jōmon people enjoyed a relatively “sedentary” lifestyle and this era coincides with the production of the most extraordinary examples of their pottery. This period roughly predates or is contemporaneous with the beginning of the Archaic or Early Dynastic period of Egypt, before the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza. About the time the Jōmon people reached the zenith of creativity, the climate in Japan, and indeed globally, was experiencing a warming trend. This change in climate would have caused sea levels to rise, forcing the Jōmon to move farther inland, and the temperate forests of Japan would have begun to produce abundant fruits, nuts, etc. This is seen as one of the primary reasons why the Jōmon could have established villages far from the sea. It seems reasonable to assume villages by the sea would be possible for bands of hunter-gatherers, but the mountainous interior of Japan would usually not be so productive as to allow for semi-permanent settlements. Indeed, it is certain that villages existed along the Japanese seashores as middens of shellfish have been identified far inland, demonstrating that the seas have receded since the end of the extreme warming event. It is interesting to note that the time Jōmon people flourished roughly coincides with the drying of the Sahara and the subsequent migration of people to the Nile, where the ancient Egyptians established some of their first communities.

Why didn’t the Jōmon people adopt agriculture? First, there were no indigenous cereal grains that could sustain them. Rice arrived with the ancestors of the modern Japanese as they made their way from the asian mainland, yet, it appears that the Jōmon continued to thrive as hunter-gatherers despite this revolutionary development. Second, at the height of their cultural complexity, which we assume accompanied their best historical living conditions, there was no need for agriculture. The natural world provided everything they needed in order to thrive. In recent centuries, many surviving groups of hunter-gatherers resisted abandoning their ways of life in the forests, deserts and arctic tundra. Because these habitats had sustained their ancestors for millennia, they saw no reason for change. The introduction of cereal grains to such people would probably have been pointless. In fact, when forced to change, the results have often been disastrous, that is, indigenous peoples, when forced to give up their traditional ways of life, often experience extreme declines in health and well-being.

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Shiseki Umenokiiseki Park

By Shiseki Umenokiiseki Park

Due to warming climatic conditions starting some 6,000 years ago, and the rudimentary practice of planting food-bearing trees and plants nearby their settlements, the Jōmon people enjoyed a relatively “sedentary” lifestyle and this era coincides with the production of the most extraordinary examples of their pottery. This period roughly predates or is contemporaneous with the beginning of the Archaic or Early Dynastic period of Egypt, before the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza. About the time the Jōmon people reached the zenith of creativity, the climate in Japan, and indeed globally, was experiencing a warming trend. This change in climate would have caused sea levels to rise, forcing the Jōmon to move farther inland, and the temperate forests of Japan would have begun to produce abundant fruits, nuts, etc. This is seen as one of the primary reasons why the Jōmon could have established villages far from the sea. It seems reasonable to assume villages by the sea would be possible for bands of hunter-gatherers, but the mountainous interior of Japan would usually not be so productive as to allow for semi-permanent settlements. Indeed, it is certain that villages existed along the Japanese seashores as middens of shellfish have been identified far inland, demonstrating that the seas have receded since the end of the extreme warming event. It is interesting to note that the time Jōmon people flourished roughly coincides with the drying of the Sahara and the subsequent migration of people to the Nile, where the ancient Egyptians established some of their first communities.

Why didn’t the Jōmon people adopt agriculture? First, there were no indigenous cereal grains that could sustain them. Rice arrived with the ancestors of the modern Japanese as they made their way from the asian mainland, yet, it appears that the Jōmon continued to thrive as hunter-gatherers despite this revolutionary development. Second, at the height of their cultural complexity, which we assume accompanied their best historical living conditions, there was no need for agriculture. The natural world provided everything they needed in order to thrive. In recent centuries, many surviving groups of hunter-gatherers resisted abandoning their ways of life in the forests, deserts and arctic tundra. Because these habitats had sustained their ancestors for millennia, they saw no reason for change. The introduction of cereal grains to such people would probably have been pointless. In fact, when forced to change, the results have often been disastrous, that is, indigenous peoples, when forced to give up their traditional ways of life, often experience extreme declines in health and well-being.