Today, we will discuss an extraordinary story: how a humble sea snail, the Cowrie shaped the fate of millions and became a currency that drove the slavetrade in British India.

For centuries, the cowrie was not merely an ocean curiosity; it was theengine behind a brutal trade in human beings. 1s

Before coins and paper money, cowries were prized for durability,portability, and difficulty to counterfeit. They became the currency of choiceacross East Africa and South Asia, including India. Even as metal coinsemerged, cowries persisted as a subaltern monetary system. Traders in Indiacould purchase everything from rice to silk with these shells, and their valuewas woven into daily language and culture. Even today, the phrase “do kaudi kaaadmi”—meaning a person of little worth—echoes this history.

From the 16th century, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and English merchantsbegan using cowries to buy slaves from African brokers. The Maldives, being theextensive breeding grounds, supplied Bengal with cowries, which were thenexchanged for human lives. A single slave could be purchased for around 25,000cowries, then.

Kolkata became a major slave trading port, alongside cities like Boston andBristol. Slave markets thrived on Chitpore and Budge-Budge, 1s with slaves arriving byships, destined for households across India and beyond. Both men and women weresold, some as domestic servants, others forced into labour or worse.

The cowrie was also a symbol of status and prosperity, even permeatingmythology. In Bengal, a bankrupt person was called ‘Kapardak sunyo’, one withzero cowries. Cowries adorned jewellery, played roles in religious rituals, andwere offered to the goddess Lakshmi.

In 1843, Slavery was outlawed in India, and metal coins gradually replacedcowries.

Now, the cowrie lies quietly in tidal pools, a mute witness to a darkpast.

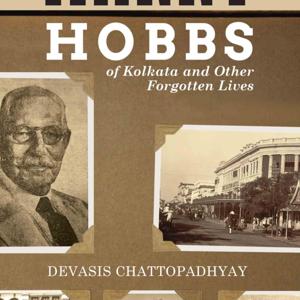

This story is from ‘Harry Hobbs of Kolkata and Other Forgotten Lives’ byDevasis Chattopadhyay.

Thank you for listening.