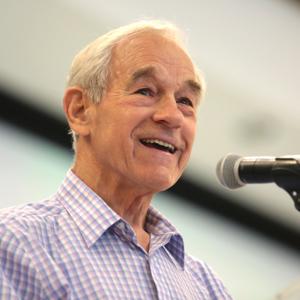

By Peter C. Gøtzsche at Brownstone dot org

The outcomes used in psychiatric drug trials are not meaningful, and psychiatric diagnoses and names of drug classes are also problematic. According to DSM-5, major depression "causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning." 1, It is the other way around.

People become depressed because they have difficulties in their lives, not because they are attacked by some depression monster that can be killed with so-called antidepressants, like antibiotics that can kill bacteria.

The patients want to have normal levels of functioning and to enjoy a meaningful life. 2, Yet, I have not seen a single placebo-controlled trial of depression drugs that reported on such outcomes except one, which was unethical because the drugs were abruptly withdrawn in half the patients, which harmed them substantially, as they developed abstinence symptoms. 3, Patients on paroxetine reported statistically significant deterioration in functioning at work, relationships, social activities, and

overall functioning.

The study was sponsored by Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of fluoxetine, which has an active metabolite with a half-life of one to two weeks. Thus, little harm will be done to patients on fluoxetine during a five-day period where the drug was changed to placebo unbeknownst to the patients.

The outcomes in psychiatric drug trials are measured on rating scales even though the results cannot tell us whether the patients have improved in any way that is important for them.

But we can exclude this possibility because the effects obtained with such scales are considerably lower than the least clinically relevant difference to placebo, both for depression drugs and psychosis drugs. 4, Thus, the drugs don't work, not even for very severe degrees of depression. 4, This is not what the patients are being told.

Statistical Hocus Pocus

We constantly hear about large effects of psychiatric drugs. This is usually because data on a ranking scale are dichotomised into the number of patients improved in an act of statistical hocus pocus.

A recent anonymous editorial in the Lancet illustrates this. 5, It quoted a 2018 network meta-analysis by Cipriani et al., 6, noting that "all antidepressants are more efficacious than placebo in adults with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, with odds ratios ranging between 2.23 and 1.37" (there was no average for all the drugs in the meta-analysis but it would have been around 1.7).

An almost doubling of the response rate looks very impressive but it wasn't. 7, Cipriani et al. also reported that the standardised mean difference was only 0.30, similar to other meta-analyses. 8, 9.

The difference to placebo is only about 2 on the Hamilton depression scale, 6, and 8 through 10, far less than what is clinically relevant. The smallest effect that can be perceived on this scale is 5 to 6, 11, and the minimal clinically relevant effect is of course larger than the bare minimum that can be perceived.

It is highly misleading to dichotomise data on a ranking scale and report on patients who have improved by a certain amount. This statistical hocus pocus spins straw into gold transforming ineffectiveness into the much-trumpeted idea that antidepressants work, 12, as expressed in a headline in the Guardian when the Cipriani meta-analysis was published. 13, By categorising people into responders and non-responders, Cipriani et al.

transformed a tiny 2 point difference in depression symptoms scores, 10, into the illusion that you are twice as likely to respond if you take a depression drug compared to placebo.

The "response" that is reported in trials is an artificial figure constructed by categorising the data using an arbitrary cut-off point. There is no natural distinction between showing a response and not showing a response. 12, People improve to different degrees.

Unsurprisingly, statisticians have advised not to cate...

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Brownstone Institute

By Brownstone Institute