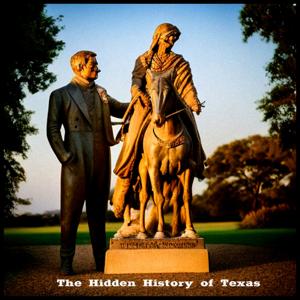

Welcome to the Hidden History of Texas. This is Episode 58 – Texans Join The Confederate Army

I’m your host and guide Hank Wilson, As always, the broadcast is brought to you by Ashby Navis and Tennyson Media Publishers, Visit AshbyNavis.com for more information.

Remember how, I talked about how prior to the actual vote for secession Texas created what was called the Committee of Public Safety? Well, in 1861 from late February through March, they authorized the recruitment of volunteer troops, to go fight for the confederacy. This was in addition to all the troops that had been recruited by Ben McCulloch, and the regiments of cavalry that were signed up by Ben’s younger brother, Henry E. McCulloch, and longtime ranger captain and explorer John S. Ford. Once the war really began with the confederates firing on Fort Sumter in April of 1861 Confederate president Jefferson Davis put out a call for volunteers. This spurred Texas authorities to begin to raise more troops for the confederacy. Then Governor Clark initially officially divided the state into six military districts which was later raised to eleven. This was designed to help encourage recruiting efforts and also to organize all the troops requested by Confederate authorities.

As 1861 drew to a close there were just about 25,000 Texans in the Confederate army. Of those, almost two-thirds of the ones who signed up served in the cavalry, which made sense due to how many Texans rode horses. In fact, it is noted that Lt. Col. Arthur Fremantle of the British Coldstream Guards, who visited Texas during the war, observed this, he said, "…it was found very difficult to raise infantry in Texas, as no Texan walks a yard if he can help it." Governor Clark even noted "the predilection of Texans for cavalry service, founded as it is upon their peerless horsemanship, is so powerful that they are unwilling in many instances to engage in service of any other description unless required by actual necessity." That love of horses is still evident today, and many Texans will either ride a horse or drive a truck rather than walk.

As the war expanded, Francis R. Lubbock, who became governor by defeating Clark by a narrow margin, worked closely with Confederate authorities to meet manpower needs. As it often is during any conflict, recruitment became more difficult as some of the early enthusiasm began to fade.

Most historians agree that the primary driving force behind the secession movement and the desire for war was the upper economic echelon of the old south. Those were the plantation and slave owners and not the regular people, much like today, it was the rich and powerful who wanted to have their way. One of the results of this was, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, there wasn’t much enthusiasm for signing up and thus in April 1862 the Confederate Congress passed a general conscription.

The conscription act declared that every white male who was between the age of 18 and 35 had an obligation to serve in the military. There was still a shortage of bodies and so in September they raised the upper age limit to 45. Then again in February of 1864, they had to expand the age limits to 17 and 50. There were few exemptions, but one of the most contentious was that if a man was conscripted then he could hire someone to serve in his place.

It is estimated that between 70,000 to 90,000 Texans served in the military and they were involved in every major skirmish except for First Manassas and Chancellorsville. At least 37 Texans also served as officers,

In November of 1863, then Governor Lubbock reported to the legislature that 90,000 Texans were in the Army. However, many historians doubt the accuracy of that number and deem it to be high. In fact, the 1860 federal census only listed 92,145 White males between the ages of 18 and 45 as state residents. Even if an allowance is made for a population increase during the war years, there may have been somewhere between 100,

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Hank Wilson

By Hank Wilson