By Yaffa Shir-Raz at Brownstone dot org.

The vote on whether to continue the universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination policy was postponed, but the discussion at ACIP exposed how, for decades, the blanket directive to vaccinate infants immediately after birth rested on assumptions, theoretical models, and partial data rather than on a solid scientific foundation.

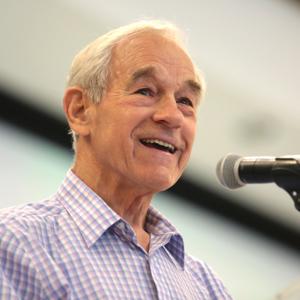

"As a father and a scientist, I do not understand how we have the courage to ask parents to vaccinate a healthy newborn at birth when the child's risk is so low and the evidence so thin. I honestly do not know where that courage comes from."

This statement by Prof. Retsef Levi during yesterday's ACIP meeting captured, with his characteristic clarity and directness, the core theme that emerged from the entire session: significant scientific gaps in a universal vaccination policy that has been in place for more than three decades in the United States.

The committee had been scheduled to vote on what seemed like technical questions: whether to eliminate universal newborn vaccination and administer the hepatitis B shot only to infants whose mothers test positive, and whether to replace the current policy, which does not allow for full informed consent, with a shared decision-making model between parents and physicians regarding vaccination later in infancy.

What surfaced during the session may have been even more important than the vote itself: for the first time, the ACIP's scientific staff presented, openly and systematically, the profound gap between the institutional narrative and the evidence base, or rather the lack of one, that underpinned an expansive policy for 30 years. They detailed how a major, far-reaching public health directive had been constructed on assumptions, theoretical frameworks, and partial datasets, absent rigorous foundational research.

Did the Birth Dose Reduce Hepatitis B Infection? The Data Say Otherwise

One of the central narratives used to justify the universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination policy was simple and compelling: the birth dose dramatically reduced hepatitis B transmission in the United States.

This narrative appeared repeatedly in CDC documents, official presentations, and public health communications.

But yesterday, perhaps for the first time so explicitly, data were presented that undermine this narrative at its core.

The sharpest and most substantial decline in hepatitis B incidence occurred between 1990 and 2007 among adults aged 20 to 49, not among infants.

Among infants and young children, case rates were extremely low to begin with, making it difficult to attribute any decline to the vaccine.

Many countries without a birth dose show similar or even lower incidence rates than the United States.

The populations that contributed most to the decline were high-risk adults, including people who inject drugs and individuals exposed via blood.

The downward trend began before the universal birth dose was introduced in 1991.

What Did Contribute to the Decline?

Several factors were presented as far more significant than the birth dose:

1. Prenatal screening and targeted intervention: When a pregnant woman is identified as hepatitis B-positive, targeted prophylaxis almost completely prevents neonatal transmission. This mechanism is evidence-based and far more effective than universal newborn vaccination.

2. Behavioral change among high-risk groups: Increased public health campaigns, risk-reduction programs, and broader access to treatment significantly reduced primary sources of transmission.

3. Improved blood screening protocols.

4. Vaccination later in childhood or adolescence: Most individuals were vaccinated in early childhood or adolescence, not at birth. These doses are far more relevant for reducing adult infection risk, since immunity from a birth dose wanes precisely at the ages when exposure risk increases.

As Prof. Levi noted, "The narrative that the policy must not be touched because it has been successful is simply ...

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Brownstone Institute

By Brownstone Institute