By David Bell at Brownstone dot org.

The Covid response was not an error, and it was not the result of rushing to address a crisis due to an unknown pathogen. It was a lot of people, mostly professionals in the field, systematically and collectively doing what they knew was wrong. It is helpful when this is systematically laid out, as such facts can form a basis from which to stop it being repeated.

Early in 2025, some statisticians from Scotland and Switzerland wrote a discussion paper with a characteristically (for Scots and Swiss) understated, even boring, title: "Some statistical aspects of the Covid-19 response." Good science is stated clearly without fanfare, while "bombshell" announcements, or similar rants indicate a need to embellish. Good data speaks for itself. However, it only speaks widely if people read it.

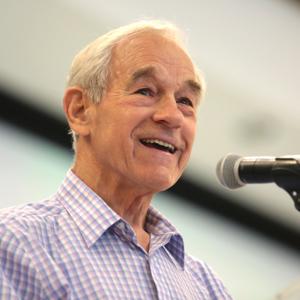

The paper, by Wood and co-authors, was written for presentation at a meeting of the Royal Statistical Society in April 2025 in London. It remains one of the best reviews of the early response to Covid - in this case with a United Kingdom focus but relevant globally. However, some people don't avidly read the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society - Series A: Statistics in Society, or attend their London meetings.

A pity, as London is nice for three days in summer and this particular Royal Society seems to have a grasp of reality lacking in some of its siblings.

The paper provides simple statistical truths, as statisticians should. Truths are particularly valuable when applied to subjects where fallacies are more profitable. This is why, in public health, they have become so rare, and therefore so worth reading. Stating truths dispassionately regarding Covid helps to grasp how bad the public health response actually was.

Covid and the Economy

Public health has always been highly dependent on economic health, so the authors set the scene by stating the obvious of the economics of the response of Western governments that decided in early 2020 that printing money was simpler than making people work to generate taxes:

Creating money while reducing real economic activity is obviously inflationary.

And consequently:

The subsequent sharp increase in inflation is one path by which the disruption has contributed to increased economic deprivation…of the sort clearly linked to substantially reduced life expectancy and quality of life.

This is important, because we knew this long before 2020 (the Romans knew it) and we also knew that the resultant economic deprivation would shorten life expectancy. This is Public Health 101, and every public health physician knew it when Covid started.

In public health, we recognize that there is a tradeoff between spending money to save one person or allocating it elsewhere to save many more. If we just spend without limit, we all get poor and then we cannot really fund healthcare at all. This is not complicated, people understand it. It is why we don't have MRI scanners in every village. We therefore make estimates of how much can save a life without overly impoverishing society and then losing more.

Wood and colleagues looked at the UK standard for this compared to the costs of lockdowns:

…any reasonable estimate of the cost per life year saved from Covid by non pharmaceutical interventions substantially exceeds the £30K per life year threshold usually applied by NICE (the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) when approving introduction of a pharmaceutical Intervention……

[Using the high 500,000 predicted mortality with minimal intervention of Neil Ferguson et al. at Imperial College, this] gives a cost per life year saved over 10 times the NICE threshold.

Again, this is basic public health. Allocating health resources is a complicated issue as it is (rightly) tied in ethics and emotion, but on a societal scale it is how we manage our health budgets. In this case, the numbers predicted to be saved through the enormous costs of lockdowns never remotely made sense.

Ho...

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Brownstone Institute

By Brownstone Institute