By Jeffrey A. Tucker at Brownstone dot org.

The year was 2001 and the dot-com bust was in the rearview mirror. New ideas were in circulation among young and visionary entrepreneurs. Sure, pets.com failed and so many others but that was a temporary boom-bust.

The Internet will change everything eventually, we were told. Technology, decentralization, crowd sourcing, and digital spontaneity will create an information landscape without gatekeepers. Everything will have to adapt. The experts of the old world will be replaced by a people's revolution. Whereas legacy elites waved credentials, a new class of revolutionaries will raise armies of servers and digits to move the center of civilization to the cloud.

Wikipedia was a headline feature, an experiment in crowd sourcing knowledge in a way that was decentralized, able to scale in ways the old model was not, and drawing from the knowledge and passions of people the world over. The platform seemed to embody the principle of freedom itself. Everyone has a voice. The truth will emerge from the seeming chaos of competing points of view.

At long last, the anti-authoritarian outlook would be tested on a medium that had intrigued scholars since the ancient world: books containing all knowledge. Reading through Aristotle's vast corpus, you find this passion and drive at work. He wanted to document everything he could about the world around him. Centuries later following the fall of Rome, St. Isidor, archbishop of Seville, embarked upon a similar path. With the help of countless scribes, he spent his life writing Etymologiae, a massive treatise on all that was known, compiled from 615-630AD.

As publishing with movable type took hold in the 15th and 16th centuries, the first similar work appeared in 1630: Johann Heinrich Alsted's Encyclopaedia Septem Tomis Distincta. When by the late 19th century, book publishing and distribution was democratized by markets and technology, and middle-class households could obtain real libraries, the encyclopedia set became a huge commercial success. Many companies were involved in making and selling them.

After the Second World War, it became common for every household to have a set on the shelf, or several. They provided endless fascination for everyone, a reference tool for learning for all ages. One of the more salient memories of my own childhood was opening them randomly and reading as much as I could, on pretty much any imaginable topic. I spent countless hours with these magical books.

Encyclopedias drew from the best experts but always with gatekeepers to decide what was and was not credible information. The top editorial position at World Book, Britannica, or Funk & Wagnalls was a powerful place to be professionally. He could decide what was and was not true, who was and was not an expert, what people did and did not need to know.

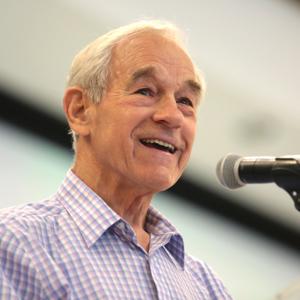

When Murray Rothbard had finished his graduate studies at Columbia University and before he had a teaching position, he was looking for ways to bring in income. As a trained economic historian, he attempted to send in three entries to an encyclopedia company. The essays were promptly rejected simply because his take was different from the mainstream consensus, never mind that what he wrote was true.

This is the problem with gatekeepers. So long as printing remained the main means by which knowledge was preserved and distributed, they would be necessary.

The founding of Wikipedia in 2001 was about a vision to change that. The initial reaction was widespread and justifiable incredulity. It could never work for anyone to be able to change anything, so they said. It's not possible simply to wipe away the gatekeepers and for truth to emerge. For years, this perception dominated, as teachers and experts of all sorts spoke of Wikipedia only with disdain.

But gradually, something interesting began to happen. It actually seemed to be working. The entries became ever more voluminous and detailed. The rules of the road became mor...

View all episodes

View all episodes

By Brownstone Institute

By Brownstone Institute